In 2018, with support from the Raith Foundation, Planact established what is known as Clusters of Community Agency, a platform made up of community leaders from informal settlements in a particular municipality. Planact has long-standing relationships with informal settlement communities across three provinces, Gauteng, Mpumalanga and the North West, where Clusters have been established.

The work Planact undertakes in communities is core to its social justice objectives, namely, to build the agency and voice of communities to self-organise, build their awareness and knowledge of their rights, and advance engagement with key stakeholders – the key being local government. This was further part of Planact’s development of new modalities to engage with local actors and public authorities.

Planact had always relied on the methodology of working closely with individual settlements to build trust and a working relationship with each community. Over time, the need for Planact’s services had increased and required an organisational restructuring of capacity and resources. It was through this strategic shift, that Planact adopted the cluster approach, a revision and rescaling of the established engagement methodology that Planact had relied on for decades.

The organisation also had to be responsive and more effectively address the acute and unique challenges these communities face, through uniting a critical mass of informal settlements into a structure to enhance their convening power and amplify the pressure applied to local authorities on development issues facing vulnerable communities.

At the start of the cluster approach, Planact collaborated with over 60 communities, spanning various provinces. Communities formed clusters through the deliberate grouping of residents with shared development challenges within the same geographic area.

The clustering approach allowed Planact to interact with multiple communities and together devise solutions that would benefit everyone in the cluster rather than a single community. This meant that the nature of the interventions was aimed at systematically addressing developmental challenges that can uplift any community facing the same circumstances. This system enabled greater effectiveness and efficiency. From Planact’s standpoint, it streamlined the communication with communities and enabled a stronger focus on the issues of informal settlement residents.

The creation of a structure also enables more systemic changes to take place. Clusters could change the situation for a community, while also bringing others into the fold to benefit from the change. Informal settlement dwellers face poor housing conditions and degraded environments. Water access and quality is an ongoing issue. Communities confront serious sanitation challenges along with electricity gaps.

In Emalahleni, Cluster leaders approached the municipality due to the lack of access to water. JoJo tanks were installed, and water trucks began to deliver water regularly a demonstration of the success of stronger collaboration with the municipality. Of significance was the fact that water delivery schedules were also provided and shared with the cluster. The cluster has also engaged and established relationships with engineers in their regions and can now report faults with JoJo tanks directly to respective engineers and officials. The ongoing engagement with the Department of Technical Services at local and district levels resulted in the rollout of chemical toilets in communities where there was previously no sanitation. The cluster is monitoring the dislodging of toilets and water delivery through schedules and documents they received from their engagements with the municipality.

Cluster leaders have received significant training from Planact to prepare and empower them with the knowledge and orientation to engage meaningfully in governance processes. The training conducted included presentations on local government legislation, and local government systems and processes. Training also incorporated modules on the Integrated Development Plan and the municipal budget cycle.

Another focus was on the Informal Settlement Guidelines. There was also a brief reference to the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Program (2009), a national housing program that advocated for the eradication of informal settlements through in-situ upgrading or relocation. Training also included a presentation on the Integrated National Electrification Program (1991), which is a national electrification program to manage electrification planning, funding and the implementation process. It aims to address electrification backlogs.

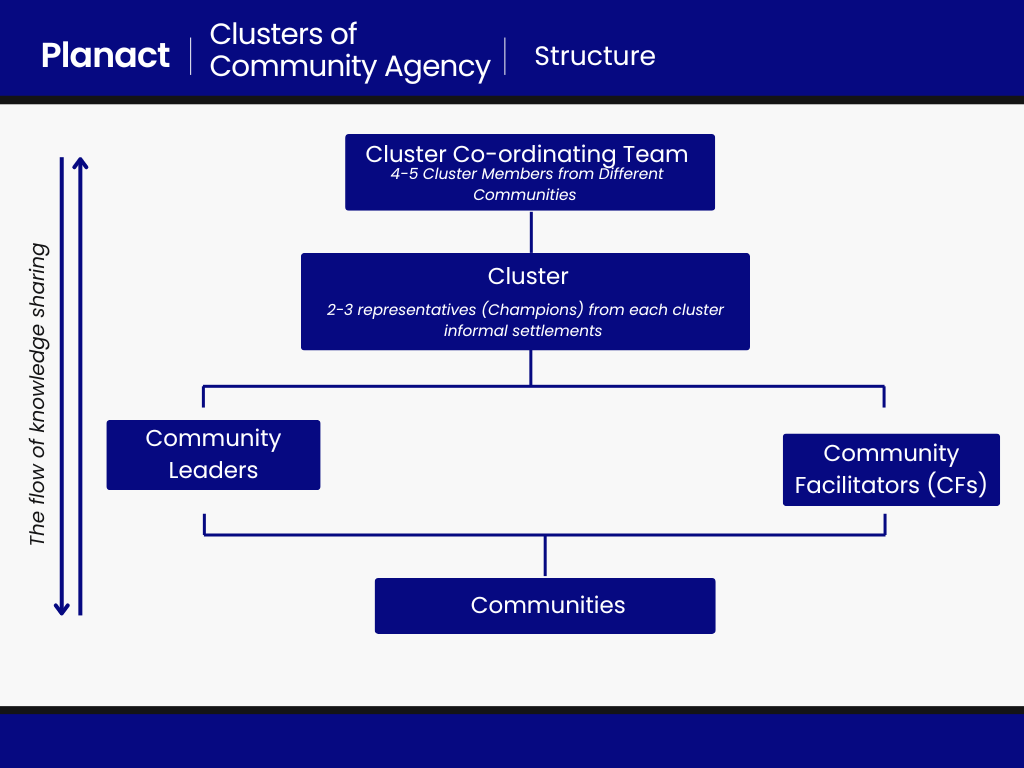

The structure and Leadership of the Clusters of Community Agency are displayed in the diagram:

The CCA model is relevant to policy and practice in South Africa in the context of rapid city expansion and in the face of the numerous drivers that lead people to pursue economic opportunity and improve their circumstances in search of services provided in cities and through population growth in urban areas.

The reality is that many find themselves in informal settlements, which are expanding fast leaving city planning far behind and the provision of housing unable to keep pace. More than 1,2 million households in South Africa live in informal settlements, without access to adequate shelter, adequate services or secure tenure.

Planact recently conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with CCA leaders and can attest to the range of service failures and challenges experienced by communities in Emalahleni, Steve Tshwete and Ekurhuleni municipalities. Land issues are mired in complexity with many settlements on private land, while in others where land was donated, community member(s) seek to profit from vacant parcels leading to instability and serious safety concerns.

Municipal regulations are often not designed with the kinds of complexity that occur in practice nor with the relevant responses. Despite this legislation is ambitious and opens the door for a closer engagement between local municipalities and communities. This is reflected in the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 captured In Government Gazette, 20 November 2000 states its intention as:

‘To provide for the core principles, mechanisms and processes that are necessary to enable municipalities to move progressively towards the social and economic upliftment of local communities, and ensure universal access to essential services that are affordable to all; to define the legal nature of a municipality as including the local community within the municipal area, working in partnership with the municipality’s political and administrative structures; to provide for how municipal powers and functions are exercised and performed; to provide for community participation.’

Planact has noted the context-specific nature of many settlements that require tailored responses and place exacting demands on municipal teams tasked with their development.

It is within this context that responses such as the CCAs offer a model to enable communities to become more engaged in their development. Planact promotes several policy responses including:

• Communities are actively involved in neighbourhood planning, development, implementation monitoring and ongoing management of maintenance.

• All residents, regardless of socio-economic status, have adequate access to reliable and affordable basic services, including infrastructure and efficient waste management.

• Tenure security for all residents is improved.

• Enhance resilience to environmental changes through innovation and partnerships.

These offer a clear advocacy pathway through which communities through the Clusters can add their voice and become active agents in the development and upgrading of their settlements. CCAs offer the opportunity to realise the goal of being part of creating thriving, people-centred, resilient, safe and functional neighbourhoods that are well-connected to the municipal fabric.